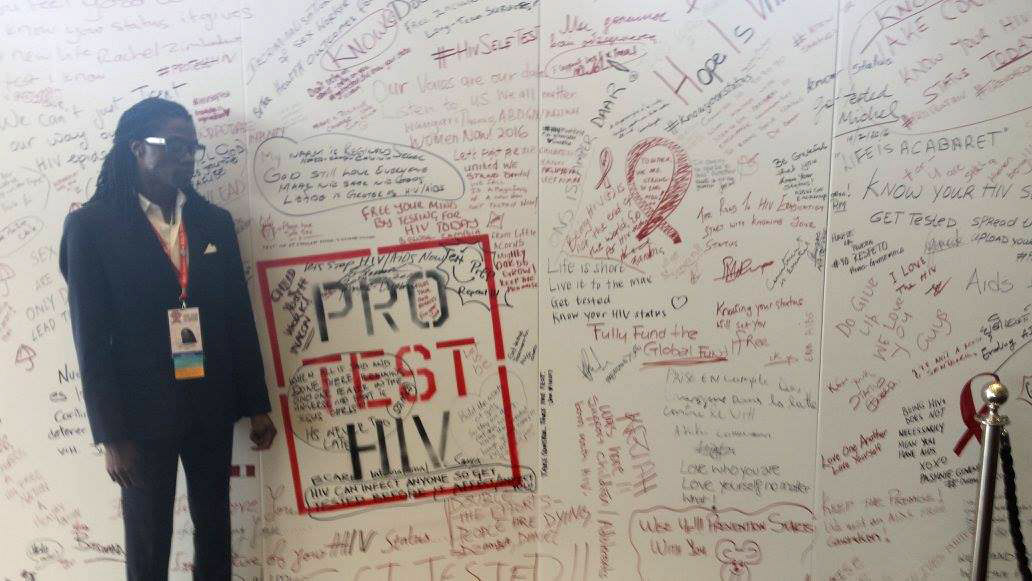

HIV: Breaking the Stigma

When Dr. Alex Washington was growing up in Memphis, Tennessee, in the 1980s, he didn’t know much about HIV/AIDS. But then a close cousin contracted the disease, and there were virtually no effective treatments.

“I remember being in his hospital room many evenings, watching his body become more frail, and hearing the doctors say different organs were shutting down,” said Washington, a professor in the School of Social Work. “I vowed to him that I would learn as much as I could about this disease and join in the fight against AIDS.”

Fast forward 30 years and anti-retroviral and other therapies have transformed HIV from a deadly disease to a chronic one. But there’s a catch – people have to get tested and many do not.

“Reports showed that young Black men who have sex with men are being disproportionately diagnosed with HIV,” Washington said, “and that they are being diagnosed later in the progression of the disease.”

Why are these men avoiding testing, and how could they be motivated to do the right thing? With his deep understanding of HIV prevention and testing, Washington was ideally suited to tackle these questions.

Armed with a nearly $400,000 grant from the National Institutes of Health, as well as funding from other sources, he began investigating the best ways to reach these men and encourage them to get tested. He soon realized this social disease required a social solution.

For Washington, this was not about a cure so much as prevention and treatment.

But before he and a team of researchers could develop the necessary tools to motivate men to get tested, they had to understand what was preventing high-risk African American men between 18 and 30 from seeking it out. The first step was simply asking.

“We conducted research to ask young Black men who have sex with men what the barriers were to HIV testing,” Washington said. “We also asked about what they perceived could be done to increase testing, what might motivate their peers to test for HIV regularly and if an intervention was developed, what it should include and how it should be delivered.”

The researchers surveyed men who had not been tested, as well as those who tested negative or positive, and found these men needed to understand their options.

“They wanted more accurate information about HIV testing and if they were to test positive they wanted to know what does testing positive look like?” Washington said. “If you’re going to design an intervention you need to provide that information.”

The surveys showed some men didn’t understand the benefits of knowing their HIV status and therefore saw no reason to seek it out. Some were concerned that, if they tested positive, the treatments would make them sick without improving their quality of life.

In addition, high-risk men were more likely to get tested if a friend went with them and knowing someone who had tested positive made them more familiar with HIV and its potential consequences. Their friends knew it wasn’t a death sentence and understood the need to test more frequently. The influence of social circles made a big difference.

In his research, Washington had to find ways to communicate accurate, yet targeted, information to move these men to take action. But even more importantly, they needed to communicate through the right channels.

The surveys showed these men wanted their information online so they could learn on their own time; videos were the ideal medium. Washington worked with Pinkerton Productions and hired Screen Actors Guild (SAG) members to make seven vignettes and tested their efficacy on focus groups. Each video covered a different theme, such as general HIV knowledge, the stigma associated with the disease and the many benefits of knowing their status. The videos were good, but the focus groups wanted shorter versions. No one was going to watch a 30-minute video; Washington realized the videos needed to be around 60 seconds in length.

While it was challenging to condense all the necessary information into such a small amounts of time, the team got it done. The result was multiple, short bursts of information on HIV that successfully caught the attention of their intended audience.

To validate the instrument further, Washington and Dr. Kevin Malotte, professor emeritus, conducted a study, testing high-risk men between 18 and 30 to see if posting the videos on Facebook would motivate them to seek testing. Participants did not know their HIV status and had not been tested for at least six months.

“Those who were exposed to the video vignettes were seven times more likely to up-take testing.” Washington said, “compared to those who just got the basic CDC materials.”

Data showing whether the social solution worked still is being gathered but early findings taken in 2017 show that those receiving the video intervention were seven times more likely to have tested for HIV than those in the control group at the six- week follow-up.

Washington’s research is making ripples far beyond Cal State Long Beach, inspiring a new generation of investigators to expand this work to other communities.

Former student Gabriel Robles was interested in studying how Latinos pursue safe sex. While taking a research methods class from Washington, the two started talking about their goal. Since their interests aligned, Washington invited Robles to help with the HIV testing outreach and other projects.

Washington also encouraged Robles to apply for an National Institutes of Health-funded Health Disparities Scholar training program grant, which helps student study health is- sues in minority communities. The application process was quite intense, but with his mentor’s support, Robles was accepted into the program. He is currently enrolled in a postdoctoral program.

“I was able to implement the work that I proposed, which is similar to Alex’s work,” said Robles. “We used similar questions in our research and made cross-comparisons between ethnic groups.”

Washington is excited to continue his research. He believes these efforts will lead to increased prevention, testing, treatment and ultimately, lives saved.

“If we can get those who are HIV positive into treatment, we can help them manage the disease,” Washington said. “For those who are HIV negative, we can direct them to take PrEP (an HIV prevention regimen) use condoms properly and consistently, and learn how to remain negative.”