Abstract

In 1921, the African-American community in Greenwood, Tulsa, Oklahoma was thriving. As a result of being deemed the most prosperous and self-determined African-American community, the community of Greenwood was known as the Black Wall Street. Jealousy and anger rooted in racism fueled the events that took place on May 31 and June 1, 1921. These events further illustrated how minorities are treated disproportionately in the criminal justice system. This paper will argue that, during the Tulsa Race Massacre, those involved in law enforcement, the criminal justice system, and the surrounding community made unethical decisions when it came to confronting their issues with the African-American community.

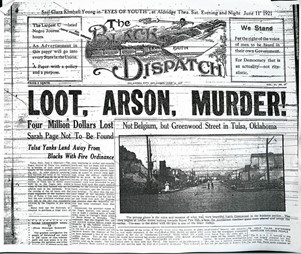

Front page of The Black Dispatch, a popular newspaper in Greenwood, OK., after the tragic attack on the town.

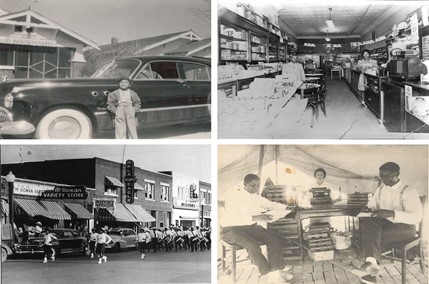

The typical day in the life of prosperous citizens of Greenwood, OK., also known as “Black Wall Street”.

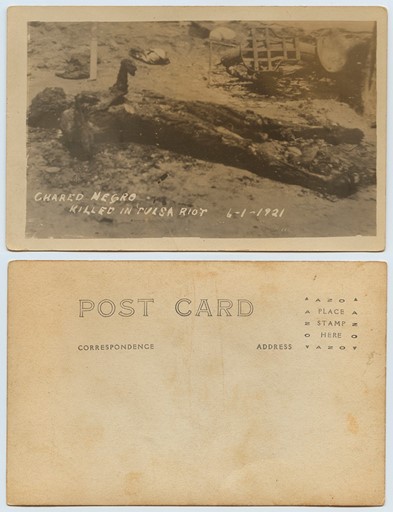

A postcard produced after the Tulsa Race Riot with a photo on the front of an African American who was burned to death. Caption reads: “Chared Negro killed in Tulsa Riot 6-1-1921”.

1921 Tulsa Massacre

Unfortunately, in today’s society, there is racism all around us, even in the criminal justice system. This has been portrayed through numerous events throughout history. There are many cases in the United States where law enforcement has treated minorities disproportionately, and the criminal justice system has failed to seek appropriate justice.

The 1921 Tulsa Massacre illustrates how African American individuals are treated inadequately by law enforcement. The events that took place perpetrated the belief that Black people were viewed differently when it came to law enforcement and the criminal justice system.

An airplane flying through Black Wall Street while dropping turpentine balls onto the tops of buildings.

White men watching from the other side of the railroad tracks as Greenwood burns down.

Black Wall Street

In the early 1900s, Greenwood in Tulsa, Oklahoma, was referred to as the “Black Wall Street.” Individuals who came from a generation of slavery were able to build and create one of the most prosperous African-American communities. Greenwood was recognized as the capital of black self-determination (History, 2021).

In 1906, wealthy African American O.W. Gurley “purchased over 40 acres of land” in Tulsa “that he made sure was only sold to other African Americans” (Fain, 2017, para. 4). Gurley provided an opportunity for African Americans to grow and leave areas of oppression (Fain, 2017). By moving to Tulsa, Black citizens were able to make a place for themselves in society and were given opportunities to build businesses (History, 2021). The ability for African Americans to build their own businesses was a huge factor in why Greenwood became so successful. During this time, African Americans were still not entirely accepted or allowed in white-owned businesses, nor were they allowed to apply their trades or purchased goods with the larger white communities (History, 2021). This created an incentive for black individuals to create their own businesses in Greenwood. Since they were not allowed to trade or do business with the white community, black individuals did business with one another. This kept the money in the black community; therefore, causing Greenwood to flourish (Fain, 2017). As a result, African Americans living in Greenwood had more opportunities than usual to advance and move up within society.

Black Wall Street prior to 1921 attack.

Although African Americans living in Greenwood were elated with how far they have come in society, white citizens did not share the same feelings. These less fortunate white people became resentful that many African Americans living in the neighboring communities were affluent and held a higher economic status than them (Fain, 2017). Activist Ida B. Wells believed white people took to lynching as a way of scaring the African Americans away due to feelings of inferiority and economic jealousy (History, 2021).

The Massacre

Events Leading Up

When Oklahoma became a state, there was an imposition of the Jim Crow laws. As a result, Black individuals in Tulsa started to lose parts of the freedom that they worked so hard to create for themselves. On May 30, 1921, African American Dick Rowland was working at his job as a shoe shiner when he had to use the restroom. Since Jim Crow laws were in place, Rowland was not allowed to use the restroom at his work, instead, he had to use the colored bathroom located on the fourth floor of the Drexil building. That same day, 17-year-old Sarah Page was working as the elevator attendant at the Drexil. While Rowland and Page were on the elevator, something caused it to jerk, resulting in Rowland bumping into her. This caused Page to scream, frightening Dick Rowland and causing him to run from the scene (Tulsa Tribune, 1921). Immediately, a clerk comforted Sarah Page, and she quickly revealed that Rowland had assaulted her while they were together in the elevator (History, 2021). The next day, police arrived at Rowland’s house, arrested him, and took him to the Tulsa County Courthouse for arraignment.

Later that day, the Tulsa Tribune (1921) published a story titled, “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator.” The article talks about how officers arrested an African American delivery boy for attempting to assault Sarah Page. However, in the article, the writer falsely mentions how Rowland “entered the elevator and attacked her, scratching her hands and face and tearing her clothes” (Tulsa Tribune, 1921, para. 4). When the public read the article, they were immediately outraged. Within several hours of the article being published, over 500 white men gathered around the courthouse, talking about plans to lynch Dick Rowland (History, 2021).

When African Americans got wind that there was a white mob gathering and conspiring to lynch Rowland, a group of armed World War I vets marched up to the front steps of the courthouse and approached the sheriff in charge of containing the mob (History, 2021). The group of African American veterans discussed with the sheriff that they were there to help in any way, but the sheriff assured them that Rowland would be safe, so they left (Krehbiel, n.d.).

The white mob outside the courthouse became enraged by seeing African Americans approach the situation and hold their firearms so confidently, so they decided they would bring back their own weapons (History, 2021). When the mob returned with their firearms and weapons, they had brought even more people back with them to the courthouse. At this point, the crowd was over 2000 people (History, 2021). During this time, a white elderly man approached a black man holding a gun, confronted him, and tried to take the gun out of the black man’s hands. During the altercation, the gun went off (Krehbiel, n.d.). The sheriff stated that it was at this moment that, “all hell broke loose” (Krehbiel, n.d., Section 6). From this point forward, the mob shifted their focus from lynching Dick Rowland to seeking out any African American they could.

The Event

After the first gunshot went off, several more followed. According to historians, a “running gun battle ensued as the black men retreated back home to Greenwood” (Extra Credits, 2020, 5:21). During this time, more law enforcement officials started to arrive at the courthouse, where they began to give out specialty badges to members of the lynch mob. One historian noted, “the police deputized some individuals from the lynch mob, and told them to ‘get a gun, and go get a n r” (History, 2021, 1:46). Police were breaking into stores, grabbing guns and ammunition, and handing it out to newly deputized mob members.

When the Black citizens of Tulsa retreated back to Greenwood, many began to line up along Greenwood’s main entrance, the Frisco Railroad tracks. Some African Americans stayed in their homes protecting their property; many African Americans lacked trust in white-owned banks so they kept their money and valuables inside their residences (Messer et al., 2018).

Additionally, many of the Black veterans went to the tower of the Mount Zion Baptist Church because it was the highest view in all of Greenwood (History, 2021).

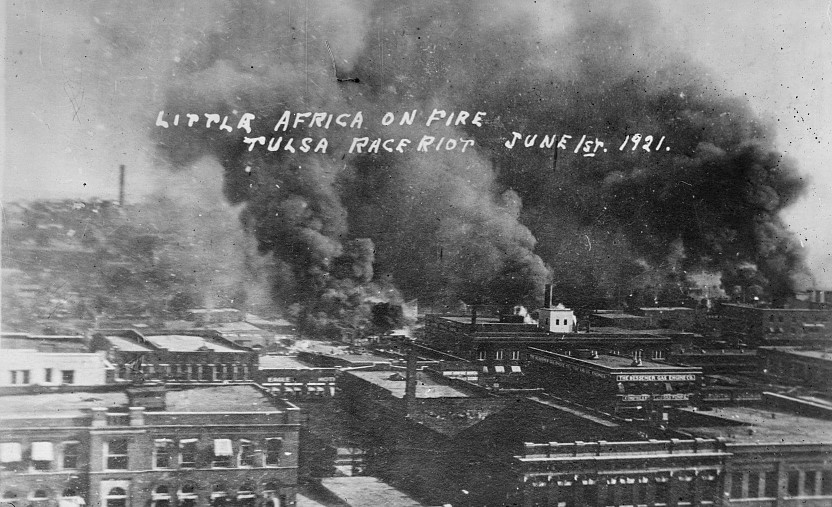

During the night of May 31st, members of the white mob tried multiple times to cross the railroad tracks into Greenwood but were met with black homeowners trying to defend their properties (Messer et al., 2018). Frustrated by not being able to get across the tracks, members of the mob organized together and rallied hundreds of white people (History, 2021). The next morning, “a force of citizens, police, and members of the national guard, numbering perhaps 1,500, moved into Greenwood,” forming a line around the perimeter of Little Africa (Krehbiel, n.d., Section 8). A little after dawn, an alarm went off in downtown Tulsa. Shortly after the alarm signaled, a full attack began on Greenwood; guns kept firing, airplanes flew above dropping turpentine balls onto the tops of buildings, members of the mob looted businesses, and white men rushed into the community, setting fire to homes, parlors, and kitchens (History, 2021). The main goal for them on June 1, 1921, was to destroy Greenwood. One of the worst parts about this event is that at no point did either the police or fire department try to intervene and stop the events unfolding before them (Messer et al., 2018).

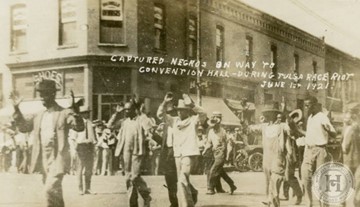

“Captured negros on way to convention hall during Tulsa Race Riot, June 1, 1921” (Tulsa Historical Society, n.d.).

Later that day, the National Guard arrived in Greenwood to help evacuate Black citizens. Many were hesitant about surrendering; however, the guardsmen convinced citizens that nothing was going to happen to them or their property if they surrendered (History, 2021). Once the individuals surrendered, they were walked to detention centers at gunpoint while the National Guard torched their property (Messer et al., 2018). While in the detention centers, African Americans were given green identification cards (Messer et al., 2018). In order to be released from a detention center, a white person must sign the green card, essentially vouching that the African American is a good, trustworthy individual (History, 2021).

The Aftermath

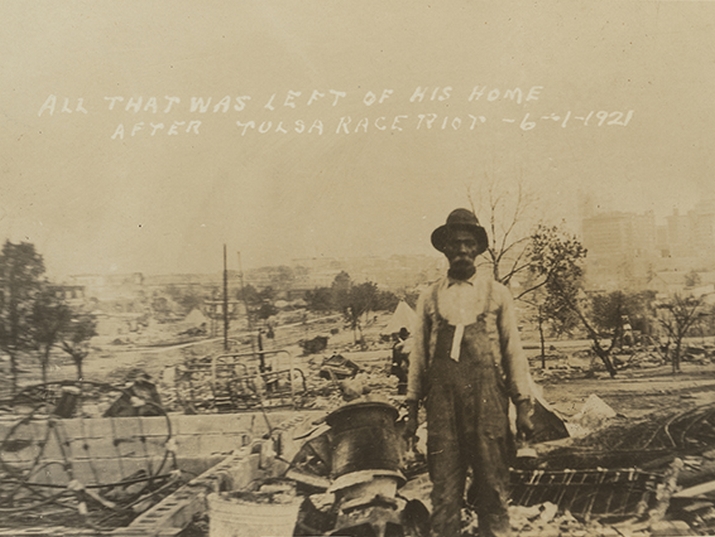

The events that took place on May 31 and June 1, 1921, were horrific and created tremendous amounts of tragedy. As a result of the race riot, the entire town of Greenwood was destroyed, leaving little to nothing for those who once called it home. More than 1,400 businesses and homes were burned, and about 10,000 African Americans were left homeless (Britannica, 2021). In addition, many individuals, mainly African Americans, were seriously wounded or killed in the attack. Official reports of the attack state that 36 people died, “10 whites and 26 African Americans,” however, many researchers believe that casualties are closer to 300 (Britannica, 2021).

The burning down of Greenwood.

The massacre that shook the world was unique because there was both a high level of property damage and influence within the Black community (Long et al., 2021). As a result of the attack, many other Black communities were afraid to grow and build communities similar to Greenwood, fearing that they would meet the same fate. The massacre became a tragic warning that Black prosperity and succession would be met with aggression and hostility. The few newspaper coverage and spread of the catastrophic event by word of mouth became a “warning that the massacre offered would have been more extensively and clearly communicated, particularly given that a sizable portion of the articles described the massacre as justified, a blessing in disguise and for the greater good of the community” (Long et al., 2021, pp.4-5). Though the damage was extensive, many insurance policies at the time did not have coverage for riot damages; therefore, compensation was not given to families whose businesses and homes were brutally burned. Although members of the community were not able to get compensated through their insurance companies, the state was able to raise money for the families who lost their possessions as a result of the attack. However, it was insignificant when compared to the millions of dollars lost.

Effects on the Criminal Justice System

The Tulsa Massacre became a reminder of how law enforcement has subconsciously deemed one group of people less important to protect and serve than another. The Tulsa police deputized mob members during the riots and continued to allow them to occur. Law enforcement used the National Guard to assist them in the detainment of innocent business owners and families, only allowing them to be released when a white person has deemed them trustworthy. The events leading up and how the government chose to handle the Tulsa Race Riots showed the nation how the United States decided to handle racial violence (Long et al., 2021). The riot itself was considered “a major policy shift in favor of nonintervention by federal and state governments” (Long et al., 2021, p. 2). According to Long et al. (2021, p. 2), “accounts of the Tulsa riot suggest that many at the time believed the government failed at all levels, and that this was a turning point in federal policy and national practice ” (Long et al., 2021, p. 2). In a sense, they are relaying the message that racially driven violence in the United States is not to be acknowledged as a heinous crime.

The catastrophic event left immense amounts of emotional and generational damage, leading to Tulsa’s homeownership and job status declining significantly within the decades following the attack. Not only did the homeownership and job status rapidly decline, but so did the interest in finding those involved in the riots. After the riots, a handful of people were arrested and charged for “looting, possession of stolen property, and arson” (Krehbiel, 2021, para. 10). Crimes like looting and possession of stolen property are both misdemeanors punishable by a year in jail, or paying a fine of $7,000. Arson, being a felony crime, would mean a definite prison time of up to 35 years or a fine of $300,000 during the time of the riots (Wirth Law Office, 2020). Few cases were taken to trial, and even fewer cases ended with the culprit pleading guilty to these misdemeanor offenses. There was no charge given for murder or nonnegligent homicide for the numerous Black lives taken during the riots that ultimately turned into a massacre.

Ethics in the Criminal Justice System

The horrendous outbreak of pure hatred and discontent that occurred over a misunderstanding is why ethics should have been applied throughout this event. Prevalent that no justice has been served for the sake of the survivors of the Tulsa Massacre, there has been no collateral compensation and very little acknowledgment by the state. Survivor Viola Ford Fletcher, who was only seven at the time of the event, remembers how vibrant and thriving her community was. She explained how different her life was when she and her family had to flee Tulsa and Greenwood (Washington Post, 2021, para. 4). Ms. Fletcher’s family, and many other families, could have had the opportunity to thrive in a Black community if there had been a reliable criminal justice system during the riots. Unfortunately, what could have turned into generational wealth and financial stability, is now a reminder of what the United States is willing to do to cover the truth about the long history of racial discrimination that has occurred, and continues to occur.

The ethics applied to policing have only recently been expanded due to the overwhelming number of police brutality and corruption within the criminal justice system. Issues like police culture were present during the Tulsa Massacre and are still present today. The attitudes, values, and norms of an institution are “accepted practices, rules and principles of conduct that are situationally applied, and generalized rationales and beliefs” (Banks, 2020, p. 19). The institutional culture of the police during 1921 was corrupt. It was flooded with criminal activity and racial discrimination. In addition, hate crimes had not begun to be thoroughly investigated until the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Before this time the local state governments were to protect the civil rights of their citizens, instead of the federal government (FBI, 2021).

The Tulsa Race Massacre was a blatant crime fueled by hatred, fear, and racial discrimination that ended in injustice. This is due to the criminal justice system’s failure at large, along with the state of Oklahoma. Police corruption is ultimately taught through the type of recruitment perspective that is emphasized by the officers in charge (Banks, 2020). For example, police Chief John Gustafson was a rotten apple who applied his personal beliefs and racial prejudice upon his fellow officers. Gustafson’s commanding officers and patrolmen deputized and enabled the white mob to brutalize and lay waste to the fully functioning and beautiful black community of Greenwood. In regard to the criminality of law, the conflict theory is viewed as an “instrument of protection for the powerful and elite, and punishment is based on non rational factors, including race and social class” (Banks, 2020, p. 107). Therefore, the threat of a shift in power that Greenwood held against the white society in Tulsa was so significant that they were able to justify the eradication of an entire community.

The only justice that was made for Greenwood has been the arrest and trial of police Chief John Gustafson, who was arraigned for the Tulsa Massacre and other charges. Not only was Gustafon indicted on five counts, “including dereliction of duty during the massacre,” he was also convicted of charges “including a car theft ring within the department and using his office to sign up clients for his private detective agency” (Krehbiel, 2021, para. 15). The trial ended in revealing how corrupt Gustafson truly was. The most astonishing detail revealed about the massacre in the trial was the eyewitness account of “Dr. A.C. Jackson’s murder and the role of law officers and Gustafson’s special deputies in the destruction of Greenwood” (Krehbiel, 2021, para. 14). Thus, solidifying the notion that the criminal justice system failed to help an entire community and race feel supported and important enough to get justice.

Aerial photo of the burning down of Greenwood, OK. Caption reads: “Little Africa on fire. Tulsa Race Riot – June 1st, 1921”.

Citizen of Greenwood standing in the debris of what was once his home. Caption reads: “All that was left of his home after Tulsa Race Riot 6-1-1921” .

Conclusion

The criminal justice system has had underlying discrimination towards people of color, particularly African Americans, since slavery and the beginning of the Jim Crow Era. Though scholars have exhaustively researched it for years, there is still the significant disproportionate treatment of minorities within the justice system. This discrimination in the criminal justice system has continuously taken away opportunities of wealth, financial stability, and prosperous lives of African American people throughout the United States. This discrimination and unethical treatment can be observed through the events leading up to the Tulsa Massacre and the aftermath. It is unfortunate how a minority-filled community, populated by intelligent and self-sufficient African-Americans, was met with great amounts of hatred, jealousy, unethical treatment, and racial discrimination. The corruption within the criminal justice system will only worsen unless society can come to the conclusion that the core beliefs of the system is to protect and serve all people no matter their differences.

References

Banks, C. L. (2020). Criminal Justice Ethics: Theory and Practice (5th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopedia (2021, June 30). Tulsa race massacre of 1921. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Tulsa-race-massacre-of-1921

Extra Credits. (2020, July 3). The burning of black wall street – Tulsa, OK – Extra history [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nc7lXBL9mng&t=336s

Fain, K. (2017, July 5). The devastation of black wall street. JStor Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/the-devastation-of-black-wall-street/

FBI. (2021, July 19). Hate Crimes. Federal Bureau of Investigation. https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/civil-rights/hate-crimes

Greenwood Cultural Center (2021). [Photograph of a parade held in the Oklahoma neighborhood during the 1930s or ‘40s]. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/ history/black-wall-streets-second-destruction-180977871/

Krehbiel, R. (n.d.). The questions that remain. Tulsa World. http://www.tulsaworld.com/app/race-riot/timeline.html#number10

Krehbiel, R. (2021, July 6). Tulsa Race Massacre: In aftermath, no one prosecuted for killings, and insurance claims were rejected but Greenwood preserved. Tulsa World. https:// tulsaworld.com/news/local/racemassacre/tulsa-race-massacre-in-aftermath-no-one- prosecuted-for-killings-and-insurance-claims-were-rejected/article_3ba23c3c-886d-5821-9970-02153261960a.html

Long, J., Feigenbaum, J. J., Kincaide, L., Nunn, N., Cook, J. A., & Albright, A. P. (2021). After the Burning: The Economic Effects of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. https://doi.org/10.3386/w28985

McDonnell, B. (2020). [Photograph of Tulsa Massacre fires]. The Oklahoman. https://www.oklahoman.com/article/5664689/watch-60-minutes-delves-into-the- haunting-history-of-the-1921-tulsa-race-massacre

Messer, C.M., Shriver, T.E., & Adams, A.E. (2018). The destruction of black wall street: Tulsa’s 1921 riot and the eradication of accumulated wealth. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 77(3-4), pp. 789-819.

Nelson, S., & Williams, M. (Directors). (2021). Tulsa burning: The 1921 race massacre [Film]. History; Hulu. https://www.hulu.com/series/tulsa-burning-the-1921-race-massacre

Portman, J. A. (2021, May 5). Misdemeanor Crimes: Classes and Penalties. Criminal Defense Lawyer https://www.criminaldefenselawyer.com/resources/misdemeanor- crimes-classes-and-penalties.htm

The Tulsa Tribune (1921, May 31). Nab negro for attacking girl in elevator. Tulsa World. https://tulsaworld.com/archive/nab-negro-for-attacking-girl-in-an-elevator/ article_758e0217-1077-5282-bdb9-4eef81f8e12d.html

Tulsa History (n.d.). [Photograph of African American men being led to the Convention Hall during the 1921 Tulsa Massacre]. Tulsa Historical Society and Museum. https://www.tulsahistory.org/exhibit/1921-tulsa-race-massacre/photos/