Bio-Inspired Solutions

As a child growing up in a small city in China, Dr. Fangyuan Tian spent most of her summers in rural areas fishing and camping with her father. She was fascinated with rocks and the smell of wild flowers.

“We are not creating new things to change the world,” said Tian quoting her father. “Instead, we are always discovering and learning from nature.” That was Tian’s first science lesson.

That casual father-daughter conversation piqued Tian’s interest in biochemistry, but she didn’t foresee a career in designing functional materials inspired by the natural world. Her love of Mother Nature and fanciful thoughts of becoming a nature explorer have led Tian to explore two areas of bio-inspired research that have the potential to improve the lives of thousands.

“You want to do more research that impacts more people,” said Tian, an assistant professor in the Chemistry and Biochemistry department.

One of her passions is developing a safe, effective and affordable material that could one day help more than a half a million heart patients each year. Inspired by a natural iron supplement, Tian has researched a biodegradable coating for stents over the past four years that would slowly release medicine into the patient following surgery without flaking.

This research has been supported by a $278,000 award from the National Science Foundation and a $15,000 award from the California State University Program for Education and Research in Biotechnology (CSUPERB).

Stents are meshed tubes that permanently prop open a clogged artery, reducing the chance of heart attacks. Biodegradable stents were developed in the 1990s with polymeric, metallic or combination scaffolding, possibly coated with an anti-proliferative drug or gene, all of which degrade over time and reduce the chances of another blockage down the road.

Tian has discovered that some initial drug-eluting stents, though, were covered in a polymer that could potentially flake off, create inflammation, and possibly trigger another blockage in other parts of the body. That’s something that she strives to correct.

Tian’s work aims to create a biodegradable coating that will release anti-proliferative and cholesterol-fighting drugs to prevent cholesterol build-up for those who are battling heart disease.

Clogged arteries greatly increase the likelihood of heart attack, stroke and even death. About 610,000 people die of heart disease in the United States every year, and about 735,000 Americans have a heart attack, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

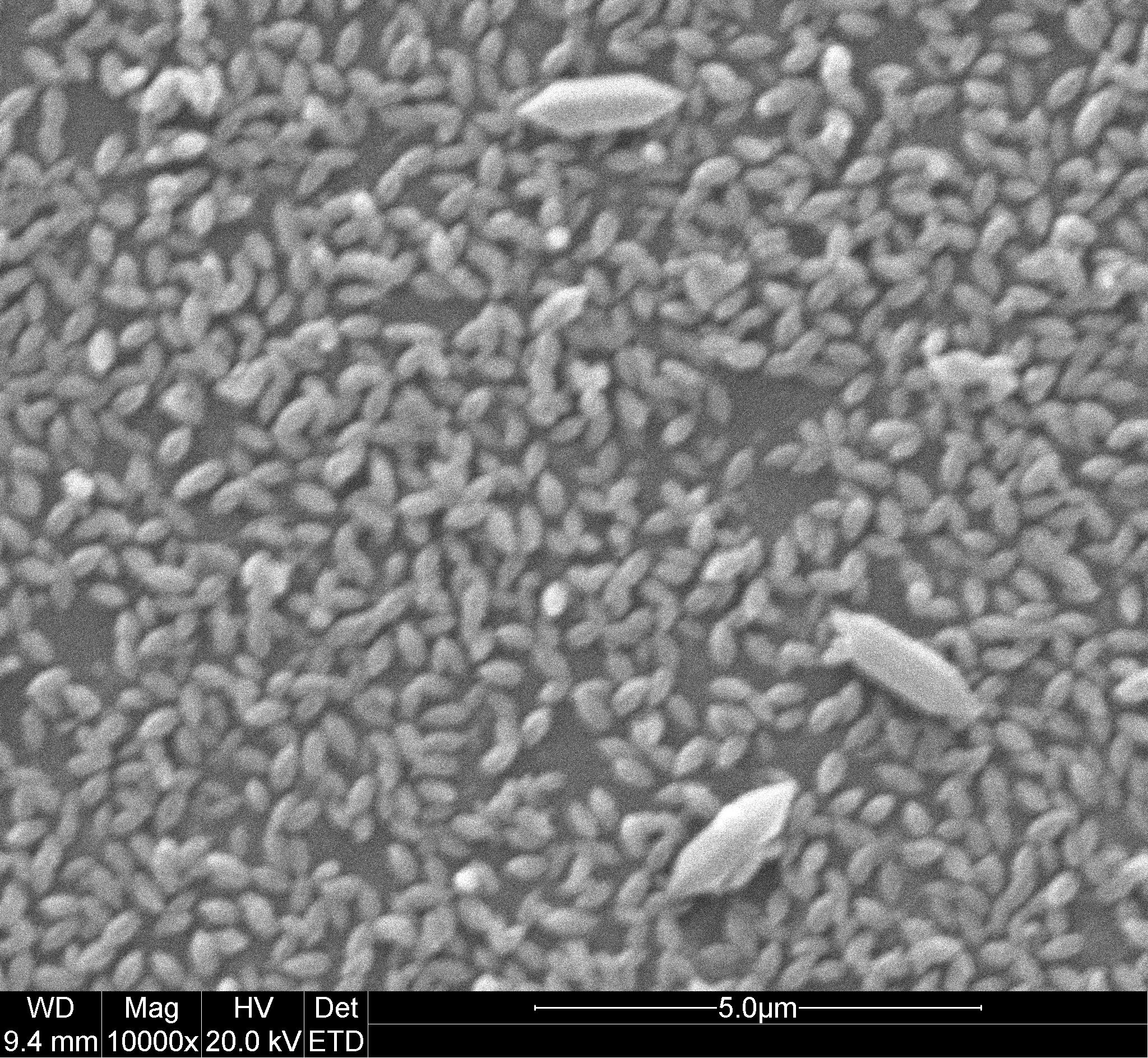

“We have developed an iron-containing porous thin film, which can be potentially used as a degradable polymer-free stent coating for a controlled drug release,” Tian said. “This material is different from other drug-eluting stent coatings, which are polymer-based.”

Student Angela Bui said working in Tian’s lab has heightened her awareness for the need of more research on drug-eluting stents.

“I get to learn new skills in fields I wouldn’t be exposed to if I didn’t do this research,” said Bui, who has researched the stent coating for two years. “It does make me feel like in some way I’m putting my mark out there.”

Besides coronary disease, Tian’s other research interest centers on solving environmental and energy-related issues. It may seem that these two disparate research areas have no relationship to one another, but Tian sees it differently.

Tian is exploring effective and more efficient new biodegradable materials — similar to the materials used in the stent — to benefit the landfill industry. Landfills are the third-largest source (14.1 percent) of human-related methane emissions in the country. Researchers, such as Tian, see this as a lost opportunity to capture a significant energy resource.

In 2017, she received a $100,000 grant from the Environmental Research & Education Foundation to support her proposal titled, “Renewable Energy from Waste: A study of landfill gas purification by hybrid porous materials.”

In this project, Tian discovered a hybrid porous material that can absorb carbon dioxide, separating it from methane. In doing so, she has found a way to more effectively and affordably filter gasses that are released as the landfill waste decomposes. The gas (methane) could be burned to generate electricity and then provided to local power grids.

“The main goal of the renewable energy project is to purify methane from landfill gas,” Tian said. “Once methane is purified with a concentration over 96 percent, it can be delivered through a pipeline to a natural gas distribution system.”

That, she said, can be used to supply community power needs for everyday use, such as cooking or powering vehicles.

-

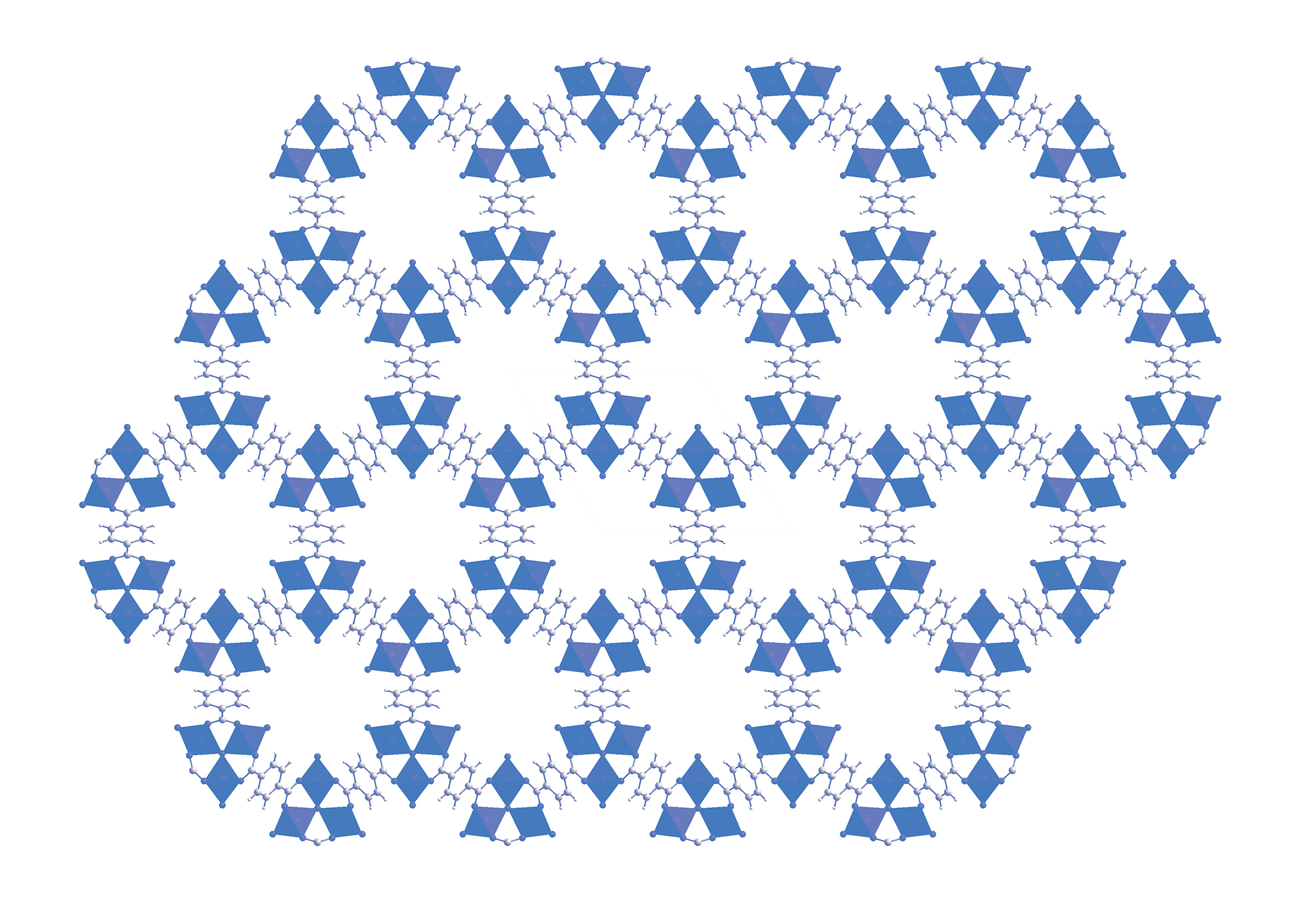

A close-up microscopic view of MIL-88B used to coat drug-eluting stents -

Another look at the MIL-88B molecule Dr. Fangyuan works with.

When Tian learned the American Chemical Society (ACS) was looking for solutions to convert methane to products with more economic benefits, she turned to nature.

In the ocean there exists a single cell organism, known as a Methanotroph, which metabolizes methane as its sole source of energy. These organisms are also common near environments where methane is produced. Their habitats include wetlands, soils, landfills and marshes.

That lightbulb moment for Tian launched a years-long passion to discover more. Along with a graduate student and nine undergraduate students, Tian utilized an award of $55,000 from the ACS Petroleum Research Foundation to explore the implantation of reactive sites to porous materials as catalysts. After screening a variety of materials, Tian and her team narrowed the results down to three as catalysts for methane conversion. Using this information, she and her team continue to explore this emerging area of environmental research.

Tian said of her twin research projects, “I feel I have the responsibility to work harder, because it could save so many people’s lives.”