Artistic Inquiry

COLLEGE OF THE ARTS

An exhibition on the intersection of science and art reveals connections with the past and the future.

Assistant Professor Dr. Paulina Pardo Gaviria is an art historian in the School of Art at CSULB. In January 2023, Dr. Pardo received the National Endowment for the Humanities’ (NEH’s) Awards for Faculty fellowship. This $15,000 grant will support Dr. Pardo’s research into the history of modern and contemporary art in Latin America and specifically fund her research for an exhibition tentatively titled Test, Observe, Analyze, Repeat: Latin American Women in Art and Science.

Dr. Pardo’s exhibition will feature her research on four Latin American women whose artistic works intersect with their own scientific work, make use of new scientific technology, or investigate the scientific efforts or policies of the governments in Latin America. The artists are all investigating how science helps us understand ourselves and how art helps us interrogate the role of government in both scientific inquiry and artistic expression.

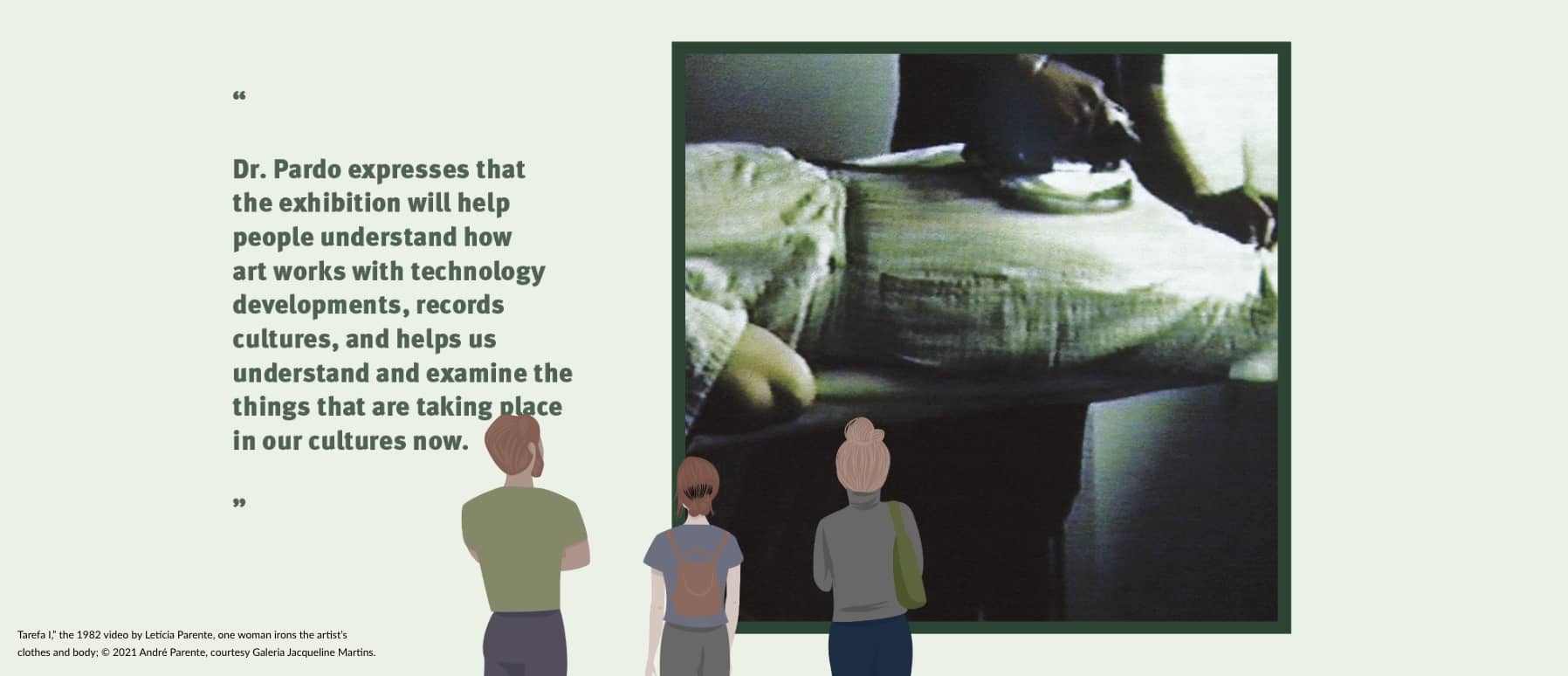

The first of the four artists, Letícia Parente, is a major focus of Dr. Pardo’s research and the subject of her forthcoming book. Parente was a Brazilian chemist who was able to earn a degree in science because of the Brazilian government’s pro-science and pro-education policy. But she was also an artist who used scientific equipment and videography to critique the same government’s civil rights violations.

Claudia Andujar is another Brazilian artist who Dr. Pardo is researching. Andujar is a photographer who lived with the Yanomami people in the Amazon and photographed them and their way of life for decades. In the 1970s, she participated in the Brazilian government’s mass-vaccination campaign by photographing the Yanomami individuals so that they could prove their vaccination status. In this way, her art intersected with science and public health as well as with authoritarian government policies.

Teresa Burga was a Peruvian artist who worked with a sociologist to survey thousands of women in Peru then displayed the data in works of art. Sandra Llano-Mejia, a Colombian artist, used medical equipment to record data on her body and then displayed that data as a self-portrait. Both women sought to record something invisible, like an EKG or a data set, then display it visually, combining scientific techniques and artistic expression to investigate how individuals, particularly women, perceive their bodies and are perceived.

One of the areas that Dr. Pardo’s research investigates is the role of government in promoting or inhibiting artistic expression and the ability to inspect that expression. Her own award from the NEH is itself an example of how the government plays that role. The types of projects that are supported and for what reasons is part of what interests her, because what counts as a mainstream art project is related to what the nation supports and what the nation thinks is important. The fact that a project about women in both STEM and art is supported by a national endowment says something about how important this is to our current time and how critical it is now. “I’m honored personally but also glad collectively that an institution like the National Endowment for the Humanities is choosing to support a project, like this one, that really brings the work of women to the front at a time when the conversations about the bodies of women are not as easy to have in different states,” says Dr. Pardo.

Dr. Pardo expresses that the exhibition will help people understand how art works with technology developments, records cultures, and helps us understand and examine the things that are taking place in our cultures now, such as the development of things like public health policies. The Brazilian government’s mass-vaccination campaign in the 1970s, for example, may sound remote, but investigating it through the prism of art history can help us to understand what is happening to us now. “We are not strangers to the shifts in public policy, certainly after the pandemic but also with political discussions that rule the bodies of women,” says Dr. Pardo. “That is why I come back to women artists, and why I think women artists have put so much emphasis on the measurement of bodies and on thinking about what a standard body is, what that means in terms of the public policies that are being applied, and how that affects us all,” she says.

Art history can expand into so many areas or disciplines, and this is what keeps Dr. Pardo engaged with it. “As an art historian, I’m not just talking about painting and sculpture, let’s say, and works that are very fixed in institutions like museums and have very little change throughout time,” says Dr. Pardo. Rather, she looks at things “that can really be connected with other disciplines and with people doing other things, with other ways of looking at the world, and [that] at the same time connect directly with our lives nowadays and look into the future.” Art history can have so many different ramifications, and this is why she looks forward to sharing the project with others through a public exhibition. Art is one lens, and art history is another lens, another tool for inspection and exploration.