What’s In Your Water?

Turn on the faucet and fill up a glass. The water looks clear and good enough to drink. But is it? When we turn on the tap, we rarely think about where the water comes from, or more importantly, what else could be lurking in the water. What the naked eye can’t see are possible pollutants from fertilizers, pesticides and gas stations that have seeped into the groundwater and end up in our drinking water or in the numerous rivers and streams that dot our state.

Dr. Benjamin Hagedorn, assistant professor in the Department of Geological Sciences, and Dr. Dessie Underwood, chair of Biological Sciences, are two professors who are helping students better understand how pollutants affect water above and below the ground.

They are researching ways to combat further abuse of our most crucial resource.

“In science, we see a problem after the development has occurred and not ahead of time,” said Hagedorn of his ongoing research.

Hagedorn said researchers should look to see whether there is a vulnerability for pollution in the future instead of reacting after the fact. Rivers, aquifers and coastal waters are not unlimited resources that can thrive with the amount of pollution that is being dumped into them.

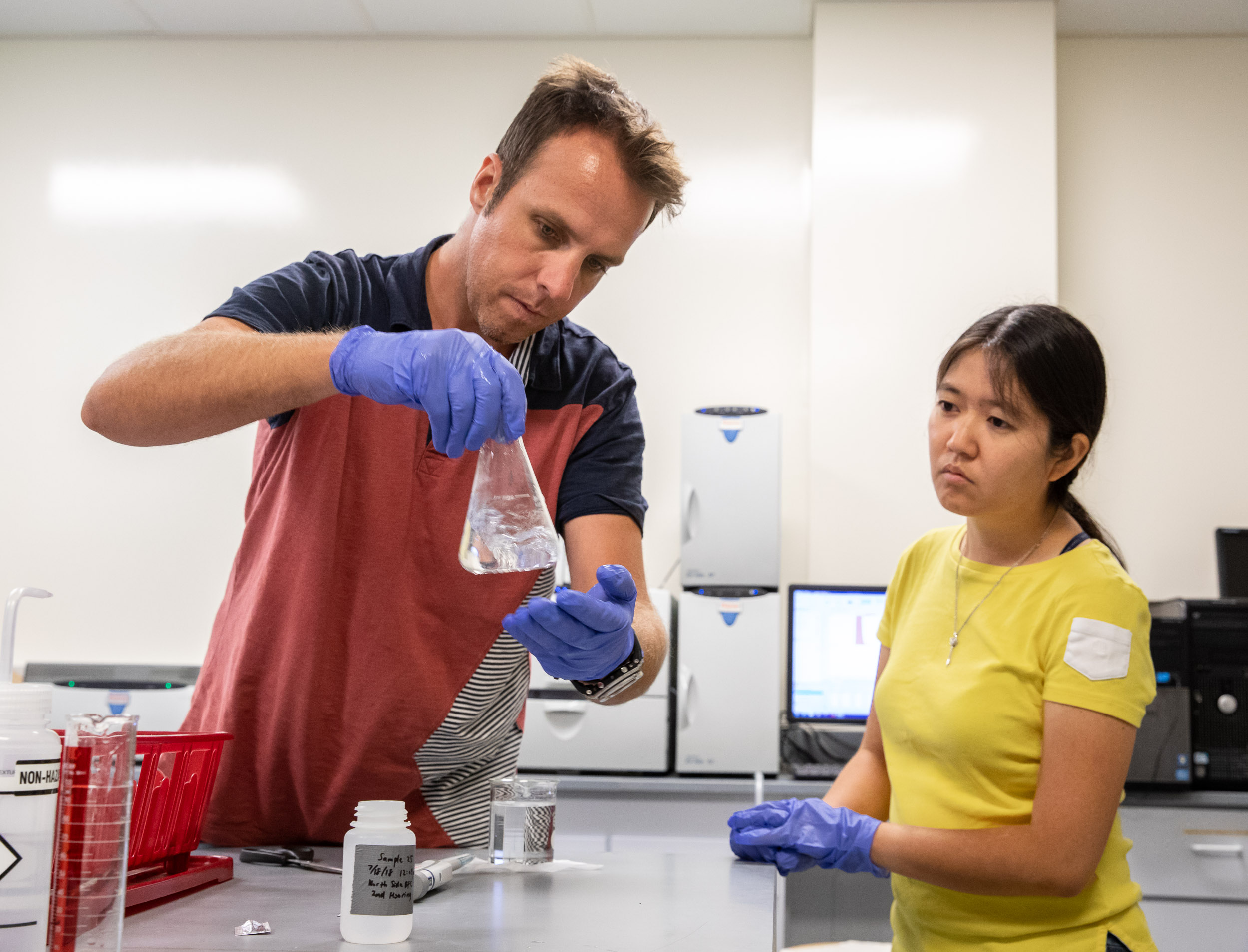

Hagedorn traces the source and the fate of pollutants in complex aquifer systems like those of Southern California. He analyzes stream, groundwater, rainfall, soil and bedrock samples in an effort to evaluate the evolution of dissolved chemicals as they migrate through the watershed.

A watershed is the common outlet where the rainfall, runoff of all streams and groundwater collect and flow into the ocean. Hagedorn routinely tests the waters along the Los Angeles coastline, while Underwood conducts ecological studies on insects and their kin in a variety of habitats, including freshwater systems, soil, urban and woodlands.

Both professors take undergraduate and graduate students to Santa Catalina Island each summer to study water runoff at the USC Wrigley Institute, where they have access to an unlimited volume of clean, high-quality seawater in the laboratories.

“The hot topic right now is avail- ability of water given the drought and climate change,” Hagedorn said.

Hagedorn said that’s just one angle his students and he are looking into. He said quality drinking water in some places, such as the recent water crisis in Flint, Michigan, and even the now-resolved issues of elevated lead levels found in the drinking water on the Cal State Long Beach campus are cause for concern.

“Ours wasn’t as bad as in Flint, but the process was the same,” he said. “The problem lies in (oxidized) water that leaches the lead from the pipes into the water. Many older buildings have not been updated with lead-free piping and that is a problem.”

Hagedorn said in California multiple pollutants related to agriculture, namely the pesticides and fertilizers that farmers use in the Central Valley eventually make it into the groundwater. He said the situation has “made the water almost undrinkable” in some areas.

“And that’s a legacy for kids to come,” he said, adding that future generations could face harsh circumstances. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has listed primary standards and treatment techniques that protect public health by limiting the levels of contaminants in drinking water. Those include microorganisms, disinfectants, inorganic and organic chemicals and radionuclides.

Hagedorn and his Environmental Geochemistry Research Group uses geochemical tracers and water balance models to study the effects of climate and land use on the Earth’s mass movements through the climate system, documenting pollutants as they travel in the air, water and soil. Early indications are that more locally sourced ground-water would help meet the demands in Southern California.

Trouble is, he said, the water is too polluted in many areas to be a sustainable source.

Hagedorn said more water could be imported from the already over-taxed Colorado River, or the state could build more desalinization plants that would increase our drinking water, but both options present challenges.

“In the Central Valley, we see evidence of subsidence, which means our ground is sinking because we pumped too much water out and it destabilizes the ground … We are essentially exceeding the sustainable groundwater yield,” he said.

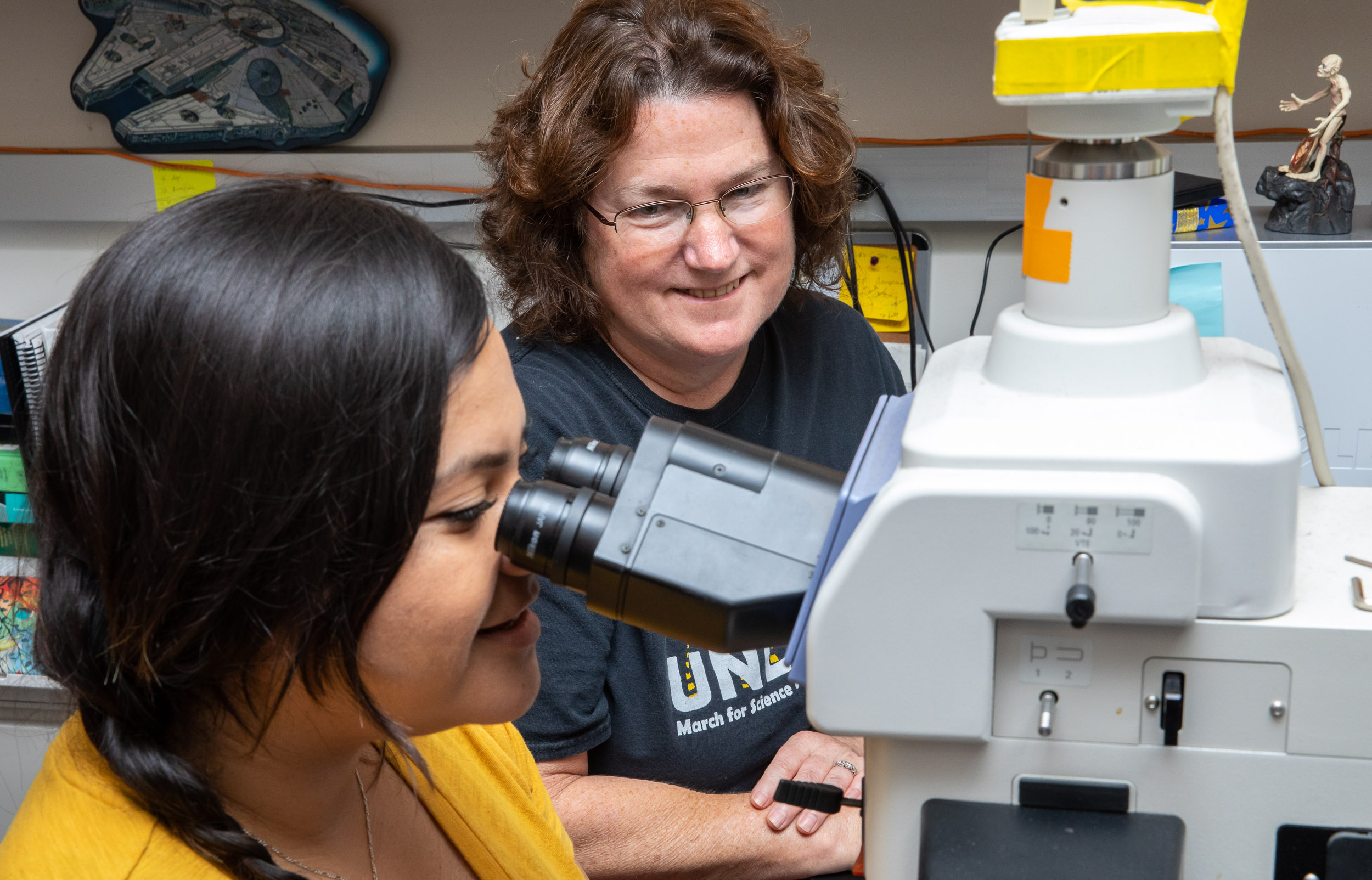

While Hagedorn’s research focuses on ground water, Underwood keeps her eye on the surface water around Southern California. Underwood and her team of undergraduate and graduate students at the Stream Ecology and Assessment Laboratory (SEAL) routinely assess the health of the freshwater streams and rivers within the Santa Ana and San Jacinto watersheds by looking at its living creatures in a variety of habitats, including freshwater systems, soil, urban, riparian and woodlands.

The SEAL team, funded by a $358,000 contract from California State Water Boards, assesses the biological health of the state’s freshwater resources while training the next generation of freshwater biologists.

“Urban streams have all this runoff from people’s yards and from the streets, so there are a lot of pollutants that end up in the streams,” Underwood said. “That will inhibit the growth of some species and let other species grow instead.

“That enables you to characterize what is living in a stream – the bugs and diatoms – and that gives you a good way of identifying the quality of that stream.”

One project SEAL took on was in 2013, when a double tanker overturned on Highway 38 and spilled an estimated 6,435 liters of diesel fuel and 14,558 liters of gasoline into Cold Creek, a small first-order tributary of the Santa Ana River

The student-led team from SEAL sampled the benthic macroinvertebrate (BMI) and diatom communities in oil-impacted stream vegetation to detect the negative impact on plant species at Cold Creek, California. Water and soil samples also were collected to evaluate the quality of the water passing through and leaving the watershed. Years later, there was still evidence of the oil in various streams and tributaries, Underwood said.

At the USC Wrigley Institute, the professors and students study the effects of pollution on our water. With Underwood leading the effort, Cal State Long Beach partnered with the Catalina Conservancy to prepare students for careers in resource management.

Underwood and her students assess the water quality in the island’s freshwater streams using diatoms. Diatoms possess several attributes that serve as biological indicators and are highly sensitive to water chemistry changes and abundant in aquatic environments. Diatoms are single-cell micro-organisms found in oceans and waterways that other creatures eat as their primary food, Underwood said. Ever slip on rock in a stream? Blame diatoms, which have adhered to the rock and made them slippery. Underwood said there are more than 1,400 types of diatoms in California, which give her team a large sample of biological indicators. The lower the number of diatoms and other bugs, the higher percentage of pollutants in the water source.

“That will inhibit the growth of some species and let other species grow instead,” Underwood said. “So, you can characterize what is living in a stream – the bugs and diatoms – and that gives you a good way of identifying the quality of that stream.

Hagedorn and undergraduate students Eliza Malakoff and Samantha Levi, along with USC faculty member Lynn Dodd, measured a chemical tracer called Radon to assess the quality of freshwater on Santa Catalina Island. By doing so, the researchers can determine how susceptible the ocean is to pollutants through runoff.

The work Malakoff and Levi performed was part of a National Science Foundation-funded grant, Research Experiences for Undergraduates.

“By measuring how much freshwater is leaving the island, we can use this as an estimate of how much freshwater is entering the island,” Hagedorn said. “This is important also to establish freshwater availability criteria for a dry-climate island like Catalina.”

Jillian Malone, a senior environmental science major who was part of the Santa Catalina Island trip, said learning where water comes from is crucial in today’s world, especially in Los Angeles.

“I feel there’s a general ignorance (by locals) toward water in Los Angeles,” Malone said. “It’s important for you to understand where our water is coming from and how it affects us.”

The research Hagedorn and Underwood are doing will enable others to feel confident the next time they turn on the faucet.