Faces of Change

These Cal State Long Beach students are working on solutions for a promising tomorrow by reaching across continents, through iron bars, and beyond socio-economic strata to make the world smarter, brighter and healthier. With their varying talents and determination, electrical engineering major Gifty Sackey, three cyclists, 52-year-old graduate student Dale Lendrum, and an aspiring teacher already have taken steps to reach their goals.

Gifty Sackey

Senior, Electrical Engineering

Gifty Sackey remembers walking through her Ghana neighborhood at night, the path dimly illuminated by candles and kerosene lanterns in the windows of the homes. She remembers how bad she felt for those others, especially the nights when she would walk into her own well-lit home, thanks to the rickety generator on the roof.

Yet not all the energy emanating from her home came from that noisy generator. Much of it came from Gifty herself, a curious child who has turned her fascination with the hum and whir of the machine above her bedroom into a successful undergraduate career in electrical engineering at Cal State Long Beach.

Gifty was 10 years old when she decided to investigate the machinations of that magical box, the one that provided electricity to she and her parents, five siblings and their spouses. She knew why they had one and her neighbors didn’t. “God is gracious,” she said of her family’s prosperity in Ghana.

Her father is a lawyer and her mother a U.S.-educated teacher, having earned her Ph.D. at Ohio State, and after several years the family was able to trade their candles for the generator.

“In Ghana, whenever the [day]light went out, my dad would fire up the generator and we would be the only house on the block with light and that was because he was able to [earn enough] and do everything,” Gifty said. “And it got to the point where I was thinking ‘What’s this generator all about?’’’

The machine intrigued her. How did the clunky metal contraption make the lights go on? What was the connection? Gifty sought out her brother-in-law, who was an electrical engineer.

“He could see my interest and he helped nurture it,” she said. “He would show me engineering designs, and at the time, I didn’t even know what a capacitor was. But he would show me and repeat the words.

“So it was repetitive conversations we had about how electricity was started out and how it’s treated that got me started. He helped me a lot and got me where I am today.”

Those early question-and-answer sessions spurred Gifty’s interest and put her on a path to receiving an undergraduate degree this spring. After graduation, Gifty will head to GE Power, most likely at their headquarters in South Carolina, and begin working on finding ways to provide electricity to various parts of the world.

Like Ghana.

“As I was leaving the country, I realized how much you take electricity for granted. At GE Power, you learn that power is generated the moment you flip a switch on the wall,” Gifty said. “That’s when the generator starts running and we expect it to work.

“But back in Ghana, we would put it on, and if it’s a lucky day [you got lights]. In that same regard, when we did run the generator it would be for only a little bit of time.”

Gifty and her family arrived in the United States a decade ago, settling in Bakersfield near her oldest sister, Carol. Carol had studied nursing in Boston and landed her first job at a hospital east of Los Angeles and that seemed like a decent spot for the extended family. Not only did Gifty, her parents and siblings come, so did their spouses.

Life in the United States was easy for Gifty, whose petite frame is outdone by her wide smile and oversized personality. She quickly acclimated to Southern California, learning English from books her mother gave she and her sisters, fashion and culture from magazines and television and taste for American food through trial and error. Sushi is not one of her favorites, but she is willing to give it another try.

“Adapting was much easier than I had anticipated,” Gifty said. “I think the educational system back home was more vigorous, the way they implement the classroom and everything else. It just seemed very laid back here. So, with that being said, I don’t think it was that hard of a transition.”

What never changed, though, was her interest in everything electrical and she continued to pester her brother-in-law for more information and her teachers at Stockdale High in Bakersfield for answers. Gifty said she always knew she would pursue a career in electrical engineering.

Yet when she began looking at colleges, her parents tempered any ideas of attending school out of state. They didn’t have the money and that meant stay close to home. So Gifty enrolled at Cal State Bakersfield, despite its lack of an engineering program.

“It was one of the hardest things, just keeping the vision alive,” Gifty said, “and knowing as an individual, I would have to strive to attain the same resources that are available to students going to engineering schools.”

After three years at Bakersfield, Gifty decided to transfer, picking CSULB for its high-level engineering program. She served as president of the National Society of Black Engineers and sought out internships.

“There were wonderful opportunities here and I was determined to take advantage of each and every single one of them,” Gifty said. She didn’t waste time finding those opportunities, either.

Dr. Mohammad Mozumdar, an assistant professor in the Electrical Engineering department, said he first met Gifty when she asked if she could join his graduate student-laden research group. She jumped right into the work, surprising Mozumdar.

“Most undergraduates are not always that interested in research,” he said, “but in the year and a half she was in my group, she worked on several different projects.”

Mozumdar said Gifty is one of those rare people who possess not only a high IQ, but a strong work ethic. Her energy and willingness to learn isn’t something that can be easily switched off.

“She’s smart and hard-working,” he said. “She likes to take the responsibility seriously and when I give her something to do, I am pretty sure she will get it done.”

The professor said he has no doubt Gifty will achieve whatever she takes on, including her goal of bringing electricity to dark corners of the world.

Brian Schwartz

Third year Economics major

Quantin Pham

Fourth year Kinesiology major

Cole Miller

Third year Business major

Brian Schwartz ran alongside his two disabled friends for years on the high school cross country team. Nothing slowed them down, not even on the hardest hills or the hottest days.

Quantin Pham watched an uncle struggled with autism and his aunt and uncle raise a child with Down Syndrome, while Cole Miller simply wanted to tag along for the ride. Watching others struggle to do simple tasks, things they took for granted led the Cal State Long Beach buddies to challenge themselves and help others through a bicycle ride. A long ride.

Journey of Hope is an annual fundraising bicycle trek across the United States that benefits Ability First Experiences, a Pi Kappa Phi philanthropy that has a chapter at CSULB.

“I have been fairly lucky in my life thus far,” said Quantin, philanthropy chair of the local chapter of Pi Kappa Phi. “I am fully capable and able-bodied, but through this…you see these kids and they live their life so happily.”

Brian watched his two high school buddies run with the same tenacity he did, but not the same physical capabilities. One guy was born without a right hand; the other had cystic fibrosis, a genetic disorder that causes severe damage to the lungs and digestive system.

Still, all three ran the same distances.

“They were such great athletes,” Brian said. “They handled their disabilities so well that most didn’t know they had disabilities. They were able to deal with it so well and act like everybody else. They never let these disabilities get in the way of enjoying life.”

Brian, like the other riders, jumped at the chance to participate in the 29th annual event.

“I can’t imagine living the way they do, just knowing the stuff they have to go through,” Brian said. “My friend with cystic fibrosis has to take 10 pills with every meal…and my other friend has one hand and can’t do some things.

“These are pretty severe conditions that you would think would impede them to live normal lives but it doesn’t at all and that really inspired me to try and do this.”

Brian added that they “made me realize that I was born very fortunate and this would be a chance for me to give back. They inspired me to give back.”

Brian and roughly 90 other fraternity brothers split into three groups. Cole and Quantin rode the North route, while Schwartz rode the southern route, which took him across the Mojave Desert, into Nevada and across states such as New Mexico, Georgia and the Carolinas. The three met up again at their destination of Washington, D.C.

Along the way, the riders would stop and visit various organizations, spending time on these “Friendship visits” with persons that had disabilities. One girl couldn’t walk or talk, but started a foundation in New Mexico that builds playgrounds for children with disabilities.

“We would make connections with people who might have autism, Down Syndrome or other disabilities – physical or mental –and you realize they are not much different than people with what we call normal abilities,” Brian said. “You would become friends with them in a matter of an hour and in another couple of hours, you would have to say good bye and it would be really sad.”

Said Cole: “You realize that people with disabilities go through stuff way worse than your worst day on a regular basis, so that makes you appreciate life a lot more.

“They also only seem to know love and compassion and kindness and happiness.”

Brian, a junior business economics major, isn’t sure where his biking experience will lead him, but said the ride changed him. Quantin agreed.

“It made me restore faith in humanity,” he said. “It made me realize that across the entire country, there are some incredible people.”

Able and disabled.

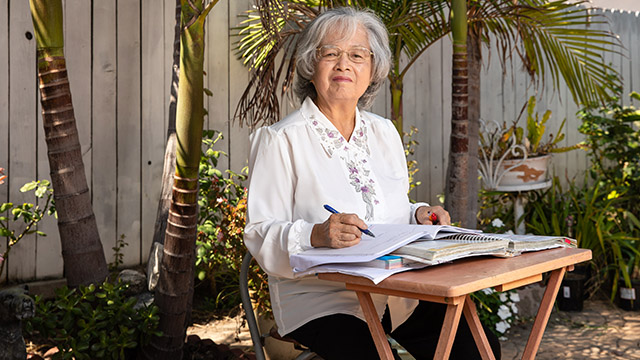

Dale Lendrum

Graduate student, Communications Studies

He crawled inside the dank dumpster to sleep. The unyielding stink of rotting garbage and prevailing darkness was preferable to what waited on the streets, predators who seek out homeless men and women at night. But the trash-filled refuge lasted only until daybreak when his drug-ravaged body screamed for the next fix.

That’s when Dale Lendrum would surface from his hiding place along Long Beach Boulevard. It would be another decade before Lendrum would emerge from that drug-induced world and go from crime to higher education. From the state prison system to the California State University system and into a future where his two worlds will eventually collide.

Lendum is a 52-year-old graduate student at Cal State Long Beach majoring in Communications Studies. After graduation his plan is to guide goal-oriented inmates through college-level courses, teaching from the very places he spent a total of 10 years of his life.

“If you are going to call yourself the department of corrections and rehabilitation, you might want to correct and rehabilitate,” Lendrum said, adding that offering a degree program would give inmates hope of a future.

Lendrum knows all about rehabilitation. It took him 28 years, six stints behind bars and one former flame before he got clean, got living and got a college degree. In 2009, he enrolled at Golden West College and eventually transferred to CSULB. He received his undergraduate degree last spring.

“There was a period for a number of years that if you went down a stretch on Long Beach Boulevard, you would find me begging by Denny’s, sleeping behind the mortuary, [or] in the dumpster area,” said Lendrum. “I’ve been one of those skeletons walking up and down those streets.”

Today, Lendrum is a healthy middle-aged man, with an easy smile, full head of wavy sandy hair who no longer hides in the shadows. The outgoing graduate student, who kids call “Mr. D”, not only is pursuing his master’s degree, he is head of statewide affairs for the Associated Students, Inc. Lobby Corps. He said once he got clean, going to college was “a no-brainer.”

ASI president Marvin Flores was caught off-guard the first time he met Lendrum.

“I was confused as to why anyone his age would want to come back to school,” Flores said. The answer is simple.

“We don’t live in a society where most people say ‘OK you paid your debt to society. Let’s give you a chance.’ We don’t live in that society anymore,” Lendrum said. “Trying to get a job as a felon is, well…there’s not rehabilitation taking place in the system,” he said.

“A convict is the last person someone wants to hire, especially since it’s so competitive nowadays. You need an education.”

Lendrum didn’t have much of a chance starting out in life. The oldest son of an alcoholic and drug addict father, Lendrum said he routinely was beaten, largely when he was trying to protect his mother from his father’s flying fist. At age 5, his father once threw up him against the ceiling, leaving a large bruise on his chest.

Lendrum eventually escaped the abuse at age 11 when his parents divorced. Free from the violence, Lendrum ran track, played basketball and baseball at Downey High School. Still, something was missing.

“I had every reason to feel good about life, I just didn’t,” he said of his teenage years. “You want your life at home, as a kid, to be harmonious. You want your parents to love each other and all that stuff. So even though I was accomplishing and doing a lot, there was one hole, one void.”

He filled that dark hollow with drugs. He took his first hit of marijuana at age 16 and his drug use escalated from there, moving onto prescription drugs, cocaine, methamphetamine and heroin. A life of crime followed.

“I think I began to experiment with drugs to feel better in my own skin,” Lendrum said.

Most of Lendrum’s jail time stemmed from theft charges and parole violations. Once, however, he was arrested for domestic violence, a charge by his then-girlfriend that made him reflect on his life. But it wasn’t enough to make him change his lifestyle.

Lendrum’s downward spiral continued, landing him on and off the streets of Long Beach. He was sleeping on a friend’s sofa when he ran into a former girlfriend from New Mexico. Turned out, Anna, was living across the street.

“I was strung out at the time,” he said. “But she drove me to my parole hearing and I ended up being taken into custody because I notoriously tested positive for drugs while I was on parole.”

Lendrum’s parole officer told him that prison wasn’t helping and offered to place him in a three-phase in-custody drug treatment program. Lendrum had walked away from drug rehabilitation centers before; this time iron bars prevented him from leaving.

Lendrum jumped at the chance to get clean. For the first time in 28 years, he had a reason – Anna, who promised they would have a change if he got clean.

After kicking his habit, Lendrum completed a two-month transitional program. It was during that phase he began toying with the idea of going to school and applied to Golden West College.

“I knew early on that I was going to have a future this late in the game, I would need to lay down a foundation and get an education,” said Lendrum, who had gotten a GED. “I knew that I would have to go out and craft something for myself.”

While pondering whether to go to college, one thought kept him awake. He was afraid that his years of drug use had caused brain damage and often wondered “would I be able to learn and retain the knowledge necessary?”

Those sleepless nights ended seven years ago when Lendrum was accepted at Golden West and began the trek from addict to student extraordinaire. He graduated from Golden West with honors, enrolled at CSULB and earned his B.A. in Interpersonal Communications. Lendrum currently is working on getting his master’s degree and preparing for a life of giving back.

“I began to see the effect and benefit of human beings helping human beings,” Lendrum said. “I began to think that if they could have that kind of an impact on me, what kind of an impact could I have? So the philosophy of giving back and paying it forward really began to take hold within me.”

Next spring, Lendrum will take the next step in his journey when he begins working long distance with Arkansas’ Likewise College, a program designed to give inmates the opportunity to pursue higher education. Lendrum said it has been shown that successful higher education programs for inmates can help reduce recidivism. More than 55 percent of inmates who complete substance abuse treatment and aftercare have succeeded in staying out of prison after three years.

Juliet Formeloza

Urban Dual Credential Program

Juliet Formeloza wanted to play basketball in elementary school, not study her lessons. She stumbled in math, unable to navigate numbers and equations with the same ease as dribbling a ball. Her grades suffered and so did her chance at making the team.

One teacher at St. Lucy’s Catholic School in Long Beach, however, took notice and began tutoring Juliet after school. After one semester, Juliet not only made the team, she brought home her best report card.

“It was just so amazing and heart-felt to see that a teacher actually cares and where they want you to succeed,” Juliet said of the individualized instruction she received.

“To see that [pride] that my parents had at that time was overwhelming,” she added.

That one teacher, Angie Gonzalez, proved to be more than a helpful teacher. She provided Juliet with the inspiration to become a teacher when she graduates with her degree from Cal State Long Beach’s College of Education next spring.

Juliet wants to help youngsters in the same way.

“She was the one that helped me the most,” said Juliet, who serves as a student-teacher at Lakeview Elementary in Santa Fe Springs, where she teaches kindergarteners.

Gonzalez recalled that Juliet was one of her most hard-working students in that fourth-grade class.

“She was always very aware of what needed to be done to improve her grades and did it without hesitation,” Gonzalez said. “Her effort, behavior and love towards her classmates was a joy to be a part of. She is a special young lady that does all she sets out to accomplish…It warms my heart that she wants to become a teacher.”

Those early tutoring sessions not only set the foundation for Juliet’s future goals, it stirred something else inside her, a deeper passion that went beyond pencils, crayons and ABCs. She has decided that she wants to teach special education and serve as an advocate for those who might not be able to fight for themselves.

“I had a family friend. He was on the spectrum of autism and I saw he had a lot of bullying. [There were friends that were bullied] even though they didn’t do anything,” she said. “It was just because they had different abilities, not disabilities. So, I would love to be that advocate for students who are trying to reach their full potential, the person who actually believes in them, who cares, too.”

“Deep inside me I just want to help,” added Juliet, who will switch to teaching special education next semester.

Rarely has Juliet followed the same path as others. Coming from a Filipino family, she was expected to either major in business or nursing. Her oldest sister graduated from CSULB with a business degree and her younger sister is a freshman majoring in business, so it wasn’t easy telling her parents she wanted to teach. Playing basketball when you stand 5-foot-1 was easier.

“It’s a cultural thing. My mom, my aunts, my cousins all worked in the health care profession,” Juliet said. “But then they finally said OK.”

Juliet said the hardest part of her college journey has been time management and keeping her stress level under control.

“I just want to be successful and get this thing going,” she said. “I don’t want to doubt myself. I want the confidence to know I can do this.”