When Art Means Life

As an incoming freshman, Christina Pecora was at a crossroads. She loved science and helping people, which made majoring in nursing attractive. But she also loved art and was good at it.

After poring over the course catalog and meeting with a counselor, she stumbled upon a solution. She would major in illustration and earn a certificate in Biomedical Art.

“It was perfect. Couldn’t believe I found it,” Pecora said. “Medical illustration was just exactly what I wanted. It was the science and the art perfectly combined.”

To earn the biomedical art certificate, students take classes in human anatomy and biology along with upper division biomedical illustration, rendering and animation classes. Prerequisites for the human anatomy class include a host of chemistry, biology and molecular courses.

Pecora was one of a handful of people taking the certificate classes, which she would soon learn was par for the course for this field.

Medical illustration, used to visually communicate complicated science, is a small niche market. Jim Dowdalls, who has taught medical illustration at Cal State Long Beach for the past 15 years, said there are roughly 500 medical illustrators in North America.

But their impact is far reaching.

“Most people don’t know what medical illustration is. The most common thing would be drawings in anatomy books,” Pecora said. But to people who ask, she also explains that medical illustrators can help design surgical tools and prosthetics, or create animations for pharmaceutical companies to show how drugs might affect a certain body part. Medical illustrations are also used as courtroom exhibits, in museums, and for a variety of educational purposes.

Pecora is currently pursuing a graduate degree in medical illustration at Augusta University in Georgia. The field is highly competitive. There are only three accredited programs in all of North America (at Johns Hopkins, University of Illinois, Chicago and Augusta) and only five to nine people get chosen from each of the three universities every year.

“Christina is hard-working and relentless. She had a clear goal of graduate school at one of the most prestigious institutions in the world, and she worked hard to make that happen,” said Dowdalls. “We at CSULB are very proud of Christina’s acceptance into the Medical Illustration program at Georgia, and know that she will be a great asset to that program.”

“Most people don’t know what medical illustration is. The most common thing would be drawings in anatomy books.”

For now, Pecora envisions herself working for a company where her illustrations can be used to educate others – whether it be for court cases or in a hospital to assist doctors with surgical techniques – and teaching medical illustration classes for fun.

“Anything that involves working with others and then helping others understand something,” Pecora said.

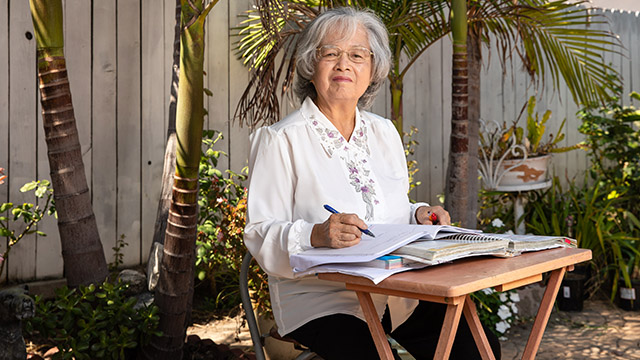

She’s already done quite a bit to help others. After graduation, Pecora spent two years building up her portfolio and completing pre-requisites for the graduate program. While in a prosection lab getting dissection experience, she met fellow CSULB alum Mia Nobles, who was working on her graduate thesis in kinesiology. The two paired up and created the first dissection manual for undergraduate students in existence.

Within the span of one semester, Nobles planned, wrote and performed dissections for the 460-page manual, while Pecora, acting as co-dissector, took photos for a photo atlas and created 190 illustrations.

“Sometimes I would draw from the photos and other times I would draw straight from the body,” Pecora explained. “I’d draw the dissections as Mia was working on them and then I would draw the finalized dissection and put it into the manual and do the layout with her writings. It was a lot of work.”

Quick sketches of Nobles dissecting would take about 30 minutes for Pecora to complete. Bigger ones that she illustrated using graphite and then scanned and digitally colored would take 25–30 hours.

The manual is currently posted to the thesis office and the duo plan to copyright the contents in order to make it available to a wide audience.

As an undergraduate student, Pecora also worked for the Learning Assistance Center as a Supplemental Instruction advisor. SI advisors facilitate sessions for high fail rate classes to help peers succeed. The role required her to attend lectures with the students and then meet in another classroom an hour and a half twice a week to go over the material and give the students tools to learn. She would also hold office hours and exchange emails.

Through it all, Pecora said her parents have been extremely supportive.

“I’m the first in the family to go to college and now a master’s, which I’m pretty stoked about, so the whole college thing for them was all new,” Pecora said.

The only time her parents have stepped in was when she was at that crucial crossroads as an undergraduate choosing a major.

“After the nursing notion was gone, I thought I would be a graphic designer, but I talked to my dad and he said it’d seem like I’d want to do something more creative,” Pecora recalled. “That’s what kind of pushed me to look for something else instead of settling. They’ve been fully supportive since.”