In The Heat of Battle

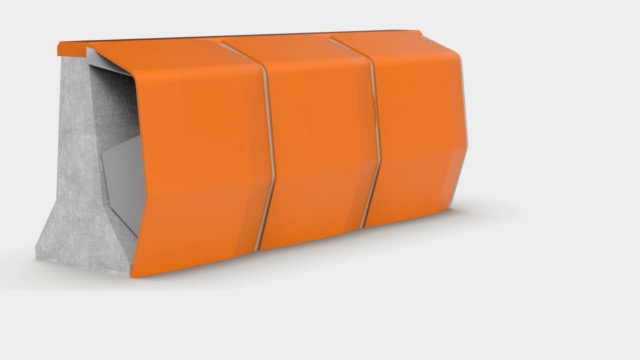

The wood and metal wedge-shaped robot sat in the corner, awaiting the green light that would signal the start of the fight. The anticipation of the impending battle coursed through Trey Roski’s body. The energy started in his toes and moved to his knees. The surge continued to travel upward until it reached the top of his head.

“That’s when you know you have accomplished something,” Roski said. “It has nothing to do with winning or losing. It’s knowing you built something. It’s all that energy.”

That feeling has resonated with Roski for roughly two decades. Happens every time he sees robots take their places in their respective corners as the cameras begin to roll on “BattleBots”, the long-running robot competition series. “BattleBots” features remote-controlled robots designed and operated by contestants in an arena combat elimination tournament setting.

Roski is producer of the popular robot-fighting show that concluded its second season on ABC TV and 17th overall.

“One of the beauties about “BattleBots” is that people can watch it and say I can do that,” Roski said.

“It’s not about girls or boys or blonde or ethics or anything else. It’s about your brain and it’s about what you can do with it. It’s about having good, clean fun where nobody gets hurt. It’s a lot of work, but you learn something, something they don’t always teach in school – how to work together.”

Roski created “BattleBots” after entering a rudimentary robot in “Robot Wars,” the precursor show to his show. “La Machine,” what he called the wedge-shape robot, destroyed the competition, giving Roski a dose of that energy-fueled euphoria.

“I fell in love with ‘Robot Wars’ and did everything in my power to make it something special, because I was a champ and got hooked and won and that evolution happened,” he said.

When the founder of Robot Wars got caught in years-long legal wrangling, Roski took the idea and expanded it. His first “BattleBots” tournament was held at the Pyramid in 1999 and streamed online, garnering 40,000 views.

“The Pyramid was new and I was familiar with it,” he said.

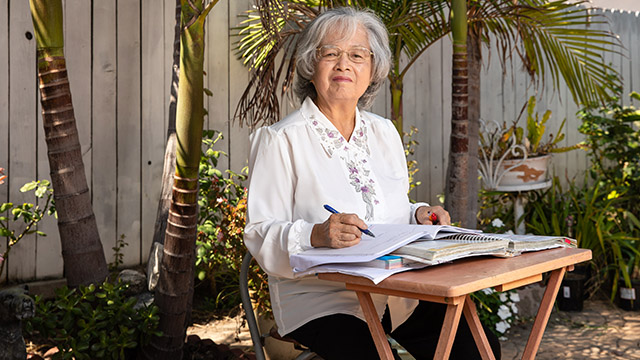

Roski graduated from Long Beach State University with a degree in finance, a career path influenced by his father, billionaire businessman Ed Roski. Getting through Long Beach State, though, wasn’t easy for Trey, who suffered from dyslexia.

Trey Roski said the professors at LBSU helped guide him through his course work, although he had to repeat some classes and it took him seven years to complete his degree.

“They (LBSU professors) gave the opportunity to succeed,” Roski said. “So much of life is about competing and that’s why I like ‘BattleBots.’ ‘BattleBots’ gives people a chance to compete and succeed and be rewarded without guilt, without negativity. The success in building a robot for ‘BattleBots’ is when you get in the ring, your robot on a red or blue square, waiting for the light to turn green to start the fight.”

Roski said robots have evolved considerably from his initial foray into the arena. His first conceptual drawing was done on a napkin. Today, 3-D printers are used to make the chassis of the robots.

“In the old days, we would use pencil and paper, sometimes napkins,” he said. “Then we would go and get the popsicle sticks and glue and motors and put it together then go buy some wood. Cut all the wood up and figure out where the motors would really go and how it would work. Then go buy the metal and start really building. Today you can do all that on a computer.”

Walter Martinez remembers the early days. The LBSU physical planning and facilities management information technology manager knew Roski from their school days. As a graduate student, Martinez entered a robot in that inaugural “BattleBots” event at the Pyramid. He later produced robots and competed in the television version of “BattleBots”, plus two other shows.

Today, Martinez lectures at LBSU and runs his own lab in Electrical Engineering. He said when he got picked to appear in the show it ignited a lifelong fascination with robots. His robot was made from parts of an electric wheelchair, metal panels and a pitch fork.

“It became an addiction,” said Martinez, who toyed with robots as a kid. “The competition is more like a sporting event, with fans and athletes.”

Today’s robots, those seen on “BattleBots”, are sophisticated machines that can weigh up to 250 pounds.

“They are cutting up each other and there are flame-throwing drones above them dropping stuff,” Roski said. “It’s the ultimate test of design and engineering.”