Weaving a Story

Look closely enough at Sovanchan Sorn’s artwork and aspects of her Cambodian family’s background can be found in every thread, in every fiber that has been woven together to tell a story. Their story. Of the killing. The fear. The hiding. The separation. Their bond.

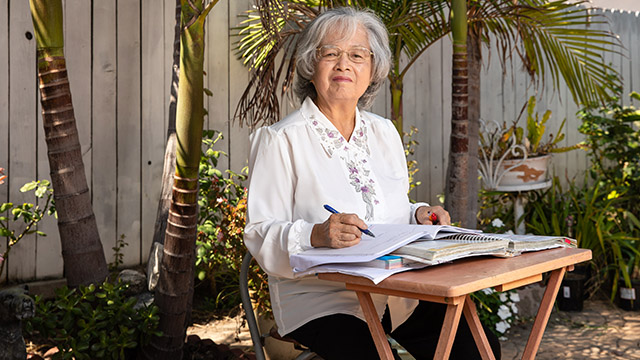

It’s Sorn’s story, too, one told through her work in Long Beach State University’s Fiber Arts program. It’s a tale that starts with her grandparents, who escaped the Khmer Rouge and a Thailand concentration camp, and eventually moved to the United States, settling in the Cambodian neighborhoods of Long Beach.

Sorn knows many families in Long Beach who suffered the same terrifying fate under the brutal Khmer Rouge regime in the 1970s. The Khmer Rouge killed an estimated 2 million people from 1974-79, and separated families. The Communist regime also abolished mainstays such as money, free markets, normal schooling, religious practices, and traditional Khmer culture.

Sorn said she wants to help heal those still affected by the atrocities through Cambodian art.

“During the war, people were killed and it (regime) not only killed people, it also killed education and the arts and the music. It wiped out our culture,” she said. “So, me doing the work I do now, I’m hoping it can help define what Cambodian art is today.”

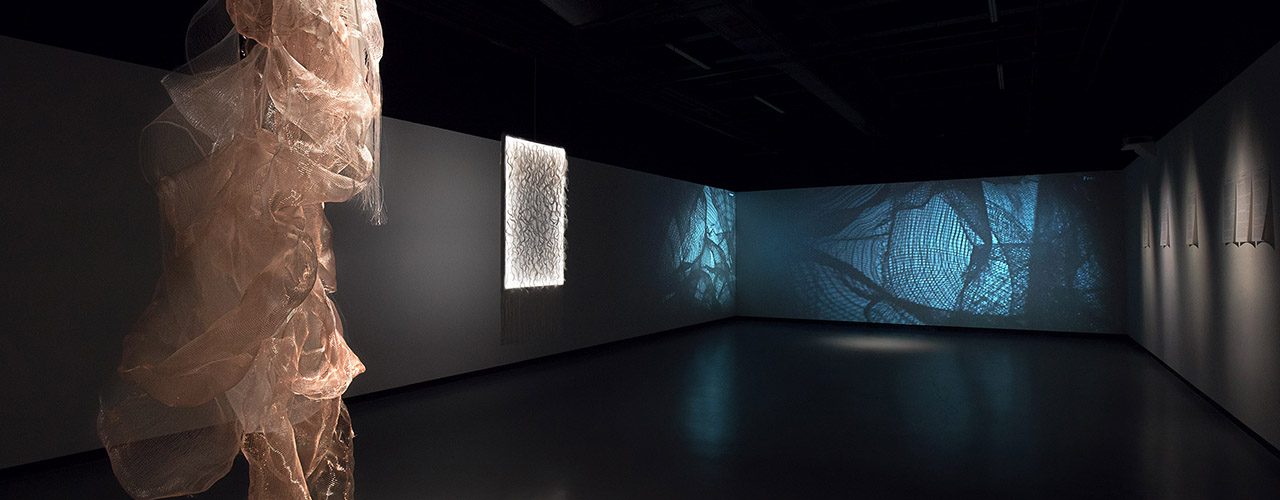

One of Sorn’s woven pieces recently hung in the University Art Museum, a double-woven silk-and-cotton piece illuminated by LED lights. She based the idea on the life cycle of a silk worm.

“The cocoon, the chrysalis. I think about my family and their life cycle and how we can break out of this together and heal,” Sorn said.

Sorn produced another piece made of copper and mono-filament that projects shadows as it spins. Voices of her grandmother, mother and two aunts emanate from overhead, reliving their days in Cambodia. She interviewed her family about their life in Cambodia for her senior project before graduating in May with a Bachelor’s of Fine Arts degree.

“It’s abstract and I’m sure people find it hard to understand how it correlates to my family’s struggles,” said Sorn, adding that the materials used represent both strength and fragility.

Sorn’s talent emerged early in her crayon drawings as a young child. It blossomed in high school as she turned to ceramics and decided art was her future. Her family, however, didn’t see the value in pretty pictures and statues.

“I don’t think they could really understand or grasp (going to college) unless you were a doctor, a nurse or teacher or lawyer,” she said. “That’s all they knew that people went to school for.

“Anytime they share (the story of) me going to college with a family friend, they say ‘Sovachan goes to school to learn drawing and painting. That’s all she knows how to do – crayons and paint.’”

While Sorn hopes to break through the barriers within her family and educate her family on western society, she doesn’t want to lose her cultural DNA. Already, she has lost some of her ability to speak in her native Khmer language; she didn’t learn English until she attended kindergarten.

“Khmer was my first language, but now I find myself slowly forgetting and I can’t do that. I can’t,” Sorn said. “I don’t want to lose that. Our culture is so beautiful and I feel being in America, and living in a western society, we can lose sight of that.”