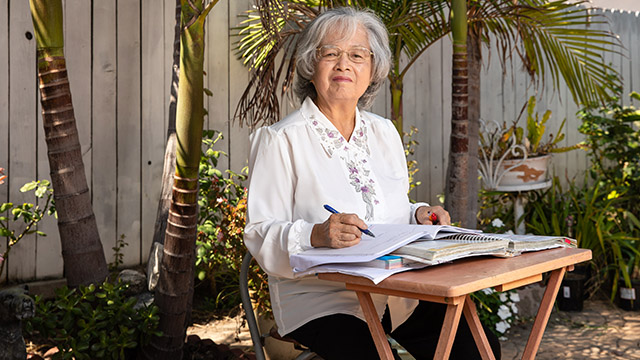

To never giving up

Lynohila Ward looked at the drab walls of the 7-by-9 cell, the armed guards and other hard-luck kids and wondered how she got there. The why was easy. Robbery, at any age, will land you behind bars.

But how did her seemingly charmed life go so wrong? She had overcome so much, more than most 17-year-olds had to face, and was staring at a bright future.

She had conquered a learning disability and speech problems, a little birth-day present from her drug-addicted mother. The last of five girls given to her grandmother to raise in a foster-care home, Ward didn’t get much attention and was left to figure life out on her own.

“I pretty much raised myself,” said Ward, whose mother returned to the streets immediately after handing the newborn to her grandmother.

As a child, Ward had stayed away from the temptations offered by the streets, spending most of her young life reading in her grandmother’s tired three-story wood house. The tough Potrero neighborhood in San Francisco was no place for children.

Her love of learning eventually would be noticed by her fifth-grade teacher, who set her on the path that brought her to Long Beach State, a place in the school’s Guardian Scholars program, and the precipice of a master’s degree. Ward is set to graduate in the spring with an advanced degree in political science and hopes to work as a news writer in the future.

“I had never stepped foot in Long Beach. I knew nothing about the school, but Long Beach was close enough where I could get home, but far away enough to get away from my environment,” she said.

According to a 2010 study by the University of Chicago, only 6 percent of former foster youths had earned a two- or four-year degree by age 24. The study showed that those not in college tend to be incarcerated, while 34 percent who had left foster care at age 17 or 18 reported being arrested by age 19. Ward was 17 when she was arrested.

Once at Long Beach State, Ward discovered the Guardian Scholars program, which assists current and former foster youth in their educational pursuits. Under the guidance of director John Hamilton, the program offers academic counseling, financial aid advising, tutoring and mentorship, among others. Ward took advantage of them all.

“When I met Lyn she was very motivated and had an abundance of energy to better her life and access the resources of the university,” Hamilton said.

“I wanted to take that motivation and energy and help her focus it. I believe this focus has made her the young woman she is today.”

Ward said Hamilton, like others in her life, refuse to let her fail. “If he sees my grades and thinks there’s something wrong, he calls me in. … He’s like another father figure in my life,” she said.

Ward never knew her father; he has been incarcerated since her birth. Her mother, whom she described as schizophrenic, rarely recognized her. Instead, Ward found other parental figures who took her under their wings. It started with her elementary school teacher, who placed her into a program that provides low-income students access to top-notch learning and the skills needed to thrive in college and life.

“There was something she (teacher) saw,” Ward said. “I was a curious kid and I liked to read a lot and she must have seen something in my academics and she recommended me for that program.”

One problem: It was a weekend program several blocks away from her home and her grandmother didn’t own a car. Ward, then age 12, hopped on a city bus to the community center alone every Saturday. Her perseverance earned a place in a private junior high and eventually a spot at an exclusive, high-end, private high school on the other side of town.

“The classroom is the one place where it’s an equal playing field for me,” she said. “The one place.”

Ward kept up with her classmates the first two years at high school. She was passing her classes, starting for the high school girls’ basketball team, hanging out with the popular kids and thinking about colleges. But a tug-of-war waged beneath her easy smile.

Was she the cool black chick who was invited to all the parties? Or was she the girl from the ‘hood whose family never had enough to eat? Not even Lyn knew the answer.

“I was in private school but also still lived in the ‘hood,” Ward said. “I had one foot on each side of fence and I couldn’t decide what I wanted to do. Did I want to be a student or did I want to be hanging out on the block? Eventually, I was doing a little of both and it was a difficult balance, especially when I started drinking and doing drugs.”

One idle afternoon, Ward joined three friends and robbed a group of girls at a San Mateo mall. They took the girls’ purses and phones, then ran. Ward and one other girl landed in juvenile hall.

“I didn’t have a job and basically, what I had learned was that there was one way of getting money and that was stealing,” Ward said.

Ward said she wasn’t scared being in the detention center.

“I was more worried that everything I had worked for was done. It was no more. I’m in here. I’m in a private school, and clearly what they are offering in juvenile hall to compared to what I’m learning in the high school is not the same. I’m going to be off track.”

Ward didn’t portray a sympathetic figure. After all, wasn’t she the one who went to the mall that day? Yet, once again, someone reached out. The parents of her best friend convinced the high school to send her classwork to juvenile hall so she wouldn’t fall behind, thus keeping her on track.

But 60-plus days behind locked doors didn’t change Ward. The pull from her neighborhood was too strong and she again got caught stealing, this time the school’s laptops. She was kicked out of school.

“I know to this day, they wished they could have done more for me, but it’s hard when I’m in my circumstances,” Ward said. “You can’t help a girl from the projects when she’s set in her ways. They did everything they could do.

“That school wasn’t a good place for students like me. You can’t put a student from extreme poverty into a private high school, one where there’s all this money. I felt definitely out of place.”

Ward felt more at home at the Life Learning Academy, a charter/continuation school founded by Delancey Street Foundation, an organization that rehabilitates ex-convicts and ex-addicts. She not only finished out her senior year, but got her first job. No more stealing.

“(The fact that) I could come from the projects and generational poverty and foster youth and all these other risk factors, and now be a grad student,” she said. “I’m doing fine.”